One thing that hasn’t changed much in the last few years is the popularity of the topic of change. The popularity and relevance of the topic has remained strong because a leader’s ability to lead people through change can often be a make-or-break contribution to a team, business unit, or entire organization.

As we point out in Contented Cows STILL Give Better Milk, much has changed in the workspace, and elsewhere, in just the last dozen years. Two wars, 9/11, a near economic meltdown, an increasingly unworkable healthcare system, high unemployment, corporate shenanigans by those who knew better, unprecedented technological development, the ubiquity of handheld communication, social media, and four generations in the workplace, not to mention having to put shampoo and toothpaste in a Ziploc bag at the airport. These are only a few of the changes that have made much of the world unrecognizable when compared to the way things were even at the beginning of the new century.

But while the context and environment in which we practice leadership has changed in material ways, the fundamentals of leadership have not. And that includes the fundamentals with which we manage change itself.

We hope you draw some comfort from our telling you that you don’t have to like change. But we’re compelled to invoke the words of former Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki, who once said, “If you don’t like change, you’re going to like irrelevance even less.”

Witness the case of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), once the second largest computer company in the world, behind IBM alone. Founded in 1957, this corporate behemoth employed more than 100,000 people at its zenith, years before it succumbed in its final tragic death throes in 1988. Founder and CEO Ken Olson’s resistance to change provides a possible clue to the company’s demise. In 1977, Olson said, from the main stage at the convention of the World Future Society that “There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in their home.”

Change, per se, isn’t inherently bad. In fact, in many cases, it’s good. It often represents progress, development, success, or the realization of some long sought after goal. Still, the anticipation of change, sometimes just the very mention of the word, more often brings pangs of apprehension than tingles of excitement.

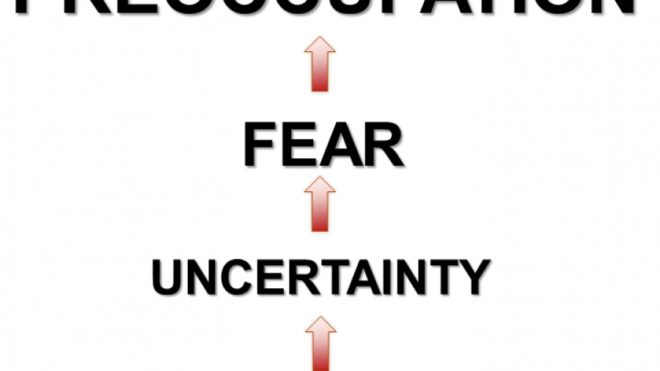

But change presents a particularly difficult obstacle to employee engagement. The diagram above illustrates.

Change breeds uncertainty. Uncertainty causes fear. Fear leads to preoccupation. And therein lies the problem, because preoccupation and engagement are mutually exclusive. I’ll say that again. Preoccupation and engagement are mutually exclusive. Although I don’t speak from personal experience, I’m told that if you’ve ever been engaged to one person while preoccupied with another, you’ll understand what I mean.

What I can relate to is that when we’re worried, or preoccupied about something at work, we can’t possibly concentrate all our effort on serving customers or beefing up the bottom line. And that portion of effort we’ll hold in reserve is the part that’s called Discretionary Effort, something we’ve written about extensively. Because it’s the most profitable morsel of effort people can offer their employers, it’s the most costly when it’s withheld.

But there’s encouraging news in this model. The one element that’s easiest for leaders to control also happens to be the one that makes the biggest difference with respect to leading change: Uncertainty. Look at the diagram. We probably can’t do much about the change itself. It’s coming, like it or not. But we can reduce or minimize the uncertainty that accompanies change, even if we can’t eliminate it altogether. How? By sharing and communicating as much information as possible, to mitigate the effects of uncertainty.

When leaders provide information about the change to come, we nip the problem at its source. Uncertainty takes a real hit, cutting off fear’s air supply, and knocking out preoccupation before it has a chance to threaten engagement.

Effective change leaders minimize uncertainty by proactively providing the following information:

* Here’s what we think the change will look like.

* Here’s why it’s happening.

* Here’s how it will affect you.

* Here’s what you can do to make it work better for everyone.

* Here’s what I’ll do to help.

Give this a try. The next time change approaches (you won’t have to wait long), formulate a communication strategy that focuses on these five information needs. Our bet is that you’ll be leading a much more willing group of people toward change that has the potential, if embraced, to take you into an even better future.

book richard or bill to speak for your meeting